No week goes by without someone talking about how negative rap music is destroying the Black community. Apparently, not just are these ignorant rappers not “real,” but they are killing our children’s minds. This line of thought always bothered me. I’d be lying if I said emcees don’t have an influence, especially on impressionable young minds, but blaming “negative” emcees for the plight of a people (a plight that is often misrepresented and sensationalized in the media) that have been marginalized for centuries is reactionary. I’m all for challenging artists to be better but if we’re worried about the effect of music on our communities, we need to invest in teaching critical thinking, creating an environment where artists own their means of production, and simply tell the truth.

No week goes by without someone talking about how negative rap music is destroying the Black community. Apparently, not just are these ignorant rappers not “real,” but they are killing our children’s minds. This line of thought always bothered me. I’d be lying if I said emcees don’t have an influence, especially on impressionable young minds, but blaming “negative” emcees for the plight of a people (a plight that is often misrepresented and sensationalized in the media) that have been marginalized for centuries is reactionary. I’m all for challenging artists to be better but if we’re worried about the effect of music on our communities, we need to invest in teaching critical thinking, creating an environment where artists own their means of production, and simply tell the truth.

The idea that our children’s minds are dependent on the content of hip-hop music sells these kids short. These kids, even the “worst of the worst,” are smart. Not to mention, if we look back to when we were kids, what are the odds that someone telling us (often with a very shallow explanation), “Don’t do that,” actually stopped us from doing that forbidden activity? In fact, it probably made us want to do it that much more. There are a number of environmental factors that play more of a role in bad behavior than the music kids are listening to. If those factors dictate that an entertainer is playing the role of parent, mentor, and/or teacher, then that is far more problematic than anything Snoop Dogg or Wiz Khalifa will ever say on a record.

I’ve been listening to music with explicit content since 3rd grade, when my mom accidentally bought me the Fugees “Blunted on Reality,” to help with a class project on Haiti. Later that year, I managed to buy Puff Daddy and the Family’s “No Way Out” and scratch off the parental guidance sticker and it was pretty much on from there. Despite my parents’ disagreement with a lot of my music choices, they made sure to always remind me of my heritage and plant the seeds for critical thought, which was another safeguard preventing me from taking too much stock in media imagery.

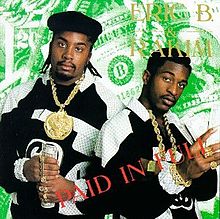

I remember going to see my family in South Carolina and showing my cousin Dee my Nelly and DMX CDs. He let me listen to Eric B & Rakim and Heavy D and they opened up my mind so I could look at music more broadly. By 7th grade I was getting into Nas, Public Enemy and Ras Kass. After a brief “purist” phase, I was bumping Mac Dre by 9th grade. Somehow, I could go back and forth between a Mos Def and an Eminem, all while taking advanced classes, reading obsessively, playing basketball and participating in a Black rite of passage group. It would seem like spending countless hours listening to Mac Dre talking about pimping and popping Thizz (“I’m not hurting nobody but my body”) didn’t bring down my grades or quality of life.

I remember going to see my family in South Carolina and showing my cousin Dee my Nelly and DMX CDs. He let me listen to Eric B & Rakim and Heavy D and they opened up my mind so I could look at music more broadly. By 7th grade I was getting into Nas, Public Enemy and Ras Kass. After a brief “purist” phase, I was bumping Mac Dre by 9th grade. Somehow, I could go back and forth between a Mos Def and an Eminem, all while taking advanced classes, reading obsessively, playing basketball and participating in a Black rite of passage group. It would seem like spending countless hours listening to Mac Dre talking about pimping and popping Thizz (“I’m not hurting nobody but my body”) didn’t bring down my grades or quality of life.

Don’t get me wrong. There are definitely things I find very problematic in hip-hop. For example, it really bothers me that many mainstream artists are playing the role of molly (what they call ecstasy nowadays) spokespeople now. However, when I reflect on my life, my decision to start smoking weed in high school wasn’t a result of listening to everyone from Snoop Dogg to Redman to Common to Talib Kweli talking about it. The first time I tried it, I was with a friend who didn’t listen to rap at all, in fact. I was curious as result of listening to his and other peers’ stories and I could never get myself to abuse my recently prescribed Prozac to get the twitch he would talk about. In his case, he picked up the activity from a cousin. Any music that was involved was merely a soundtrack.

When I hear people rail against the rampant negativity in hip-hop, I can’t help but think it’s a reaction to the lack of balance in the mainstream. What you see on TV and hear on the radio is a direct function of commercial culture. As someone that works in the media and has to track page views as part of my job, I’m well aware that those YouTube clicks and replays are very important. They determine ad revenue and what music will get corporate support. If you’re wondering why it seems like there’s an endless barrage of money, cars, clothes and guns, it’s because companies are trying to sell these things and messages about financial literacy and going to your local library don’t fit with American consumerism.

There are a select few entities that own our media outlets. Ras Kass sums it up perfectly in his track “Behind the Musick”:

“You can be the hottest MC, literally leave the mic smoking

No marketing and promotion

No 106 & Park, no TRL

Don’t kill the messenger homey but don’t expect to sell

Viacom own MTV, VH1

BET, five labels until BMG

Merged with Sony, EMI, Universal and WEA

Only four labels in the music industry bruh

All radio controlled by two companies

Just two rap magazines, read between the lines.”

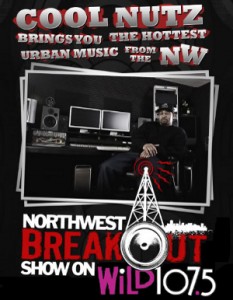

If we’re really concerned about diversifying the messages in the mainstream (aka making more positive and directly educational music easily accessible) then we have to create an environment where artists aren’t dependent on these media entities who are often tied to these corporate forces that could care less about the Black community’s welfare. An artist wouldn’t feel so much pressure to make only a certain kind of music if he had complete creative freedom. The limitations of corporate dependence are as evident in Portland as anywhere, where local hip-hop only gets mainstream play for a whopping three hours a week on Cool Nutz’ Northwest Breakout Show on Sundays from 9-12 pm (Much respect to Cool Nutz for doing his part in promoting the local entertainment economy).

This is far from a coincidence. Last year I did a three part series entitled “Hip-Hop Crackdown,” where artists who varied in content all told the same stories of having a hard time booking shows because of promoter, police, OLCC and other institutional pressures throughout the city. Ultimately, this hurts creativity because artists have to spend an inordinate amount of time just scraping by and don’t get the exposure that allows them to grow.

This is far from a coincidence. Last year I did a three part series entitled “Hip-Hop Crackdown,” where artists who varied in content all told the same stories of having a hard time booking shows because of promoter, police, OLCC and other institutional pressures throughout the city. Ultimately, this hurts creativity because artists have to spend an inordinate amount of time just scraping by and don’t get the exposure that allows them to grow.

In order to counter this, fans have to go out of their way to promote their favorite artists, buy their music, and demand and show up for their shows. It may seem trivial, but bump up their YouTube stats and “like” or “follow” them on social media. Someone is keeping track. You can even write to these artists and tell them personally how much you feel their music because chances are, most of what they’re hearing from people is criticism (Coming from a columnist, hearing a good word every now and then really does make a difference).

If there’s any positive to the plight of Portland’s hip-hop scene, it’s that many of the false divisions between different types of hip-hop aren’t very pronounced because artists have to work together just to make anything work. In theory, people should be able to put their heads and money together to create outlets outside of radio and unsupportive concert venues, in which their fans could engage and support their music.

Of course, as with any goings on in the Black community, the Willie Lynch mentality has an uncanny way of rearing its ugly head. Artists will say all the right things for the reporter or the cameras but will be at each other’s necks either directly or behind each other’s backs, often over trivial issues.

In terms of conscious artists, especially on a national level, there has been the seeming emergence of the “progressive celebrity” in hip-hop. These artists are very much like the personalities you see on MSNBC, who are great for sound bites but often lack depth and/or proactive solutions when really pushed. To spot one, just look for statements saying artists who don’t make music like them “aren’t real,” or that fans that listen to records with negativity or don’t personally support these artists are “part of the problem” (the old George W. Bush “if you’re not with us, you’re against us” mentality).

These statements do a disservice to the promotion of variety in hip-hop and more importantly, hurt individual’s credibility. Telling the truth requires nuance and complexity. Hip-hop has roots that date back to Negro spirituals. Discussions around spirituals are often (and rightfully) framed around how they were used as coded language to escape the plantation but many of these songs also served the simple purpose of helping slaves relax and take their minds away from their plight. Some people may hate the more foolish music, but chances are if you just listen to completely serious records and literally scheme on revolution 24/7, an anxiety or heart attack is in your near future.

The dueling, yet cooperative dynamics of Black music are very much evident today. Places like Pittsburgh can produce both a Jasiri X and a Wiz Khalifa (although if you listen to Jasiri, their beginnings were far more similar than one might think).

Black artists can choose to use their talents in many ways but at the end of the day, we can’t forget that this is a business and currently, we don’t own the means of production. Whether we like it or not, these artists are going to have to work together and in reality, that isn’t as much of a problem as some would think. Artists don’t want to be one-dimensional. No matter what image we put out there for others, fans certainly aren’t one-dimensional either. As Black people, we have the right to be as complex, sometimes contradictory, and full of variety as any other group. We may have been conditioned to kill ourselves over this (see: Willie Lynch mentality again) but that doesn’t have to be our reality. We really can support the entertainment we produce as a whole and create a thriving economy that isn’t dependent on the carrot and stick of established corporate powers.

Black people getting money productively is a beautiful thing so stop stressing yourself or others out for listening to Trinidad James. If you step back and look at the bigger picture, a Trinidad James and a Kendrick Lamar cover a pretty large segment of fans and potential revenue. It would be much easier to re-invest these profits if we had some sense of collectivity and cooperative economics. Why let trivial labels like “conscious” or “gangsta” stop us?