This is my new article that appears in The Skanner.

Blacks are overrepresented in Portland’s sheltered population, according to a new report by the Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness (ICPH).

“This is something that no one really wants to talk about,” says co-writer Matthew Adams. “Media attention is focused on the one percent and the middle class.”

The study, titled “Intergenerational Disparities Experienced by Black Families”, utilizes the US Census Bureau’s 2005-2009 American Community Survey data to analyze why Black families are overrepresented in US homelessness and poverty statistics.

Nationally, 23.3 percent of Black families lived in poverty in 2010, compared to only 7.1 percent of white families. To put that in perspective, one in every 141 Black family members stayed in a homeless shelter versus one in 990 white family members.

Blacks made up only 12.1 percent of the US population, but represented 38.8 percent of sheltered persons in 2010. Meanwhile, whites were 65.8 percent of the general population but only 28.6 percent of those occupying shelter beds.

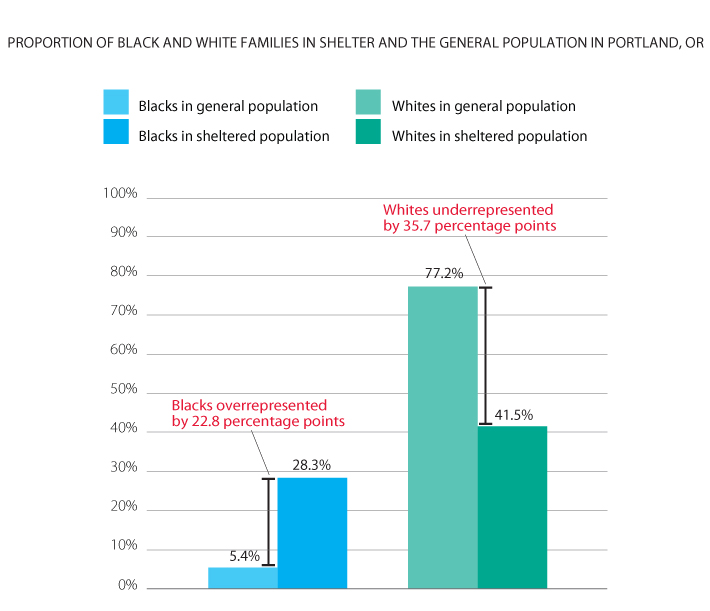

In addition to national statistics, the report also breaks down general versus sheltered populations for Blacks and whites in 37 cities, including Portland.

Although Blacks made up about 5.4 percent of Portland’s general population, they accounted for 28.3 percent of the city’s homeless. Whites, on the other hand, made up 77.2 percent of the general population and only 41.5 percent of the sheltered population. Blacks are overrepresented in the homeless population by 22.8 percent while whites are underrepresented by 35.7 percent, according to the study.

The authors of the study suggest that racial barriers to resources are the cause for these disparities.

“Homelessness has been a racial issue for a long time,” says Adams. “Sadly, people just take it as a given.”

He points to institutional racism in areas such as the prison industrial complex, housing and employment to demonstrate how race plays into poverty.

Adams notes that Blacks make up 40 percent of the US prison population. Upon release, convicted felons can legally be barred from public housing and employment. In addition, some ex-cons have to make restitution payments, which can be difficult if they’re not able to find employment.

Adams says this has an especially negative effect on children who have to deal with the possibility of having their families broken up. He notes that studies have shown children with incarcerated parents have a higher potential for developmental delays.

Half of Oregon’s Black children live in poverty, according to the Census Bureau.

The study also addresses housing discrimination.

“You had red line areas, which meant Blacks were only allowed to live in certain neighborhoods,” says Adams. “The long standing impact of this still perpetuates today.”

According to the study, the median household wealth for Blacks was $5,677 compared to $113,149 for whites (Black and white categories include data for Hispanics).

Lastly, Adams examines institutional racism in hiring.

The study found that Blacks with associates degrees had a higher unemployment rate than whites with high school diplomas (10.8 percent and 9.5 percent respectively). Also, the report says that a Black male employee with a bachelor’s degree or higher was paid 25.4 percent less on average in weekly salary ($1,010) in 2010 compared to a white male worker ($1,354) with the same education level.

“You know what they say, we’re the last ones hired and the first ones fired,” says Ibrahim Mubarak, who runs the Right 2 Dream Too camp in downtown Portland.

The camp gives people a place to sleep for 12 or more hours and refers them to social services. It allows families and couples to stay together, allows pets and doesn’t discriminate based on sexual orientation, says Mubarak.

According to him, most people come to the camp because of foreclosure, the splitting up of families and outsourcing of jobs.

He says that the camp has helped 13 people find work and eight find housing.

Although he’s seen mostly white people at Right 2 Dream Too, Mubarak has noticed how the barriers that lead to poverty can have a particularly detrimental effect on Black families. He says there are a lot of Black families couch surfing instead of staying at shelters.

“When they say they’re creating affordable housing, who can afford that housing?,” he says. “These policymakers need to sit at the table with the people that are being affected by poverty.”

Instead, Mubarak suggests that the city is using its homeless population to get funding that isn’t going to those that need it.

Currently, the city is imposing fines on the camp that start at $641 for the first two months and double every month after that.

“It’s a shame that people are not allowed the proper resources,” says Mubarak. “This is not the solution but it’s a working model for now.”